Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” resonates after a week in Vermont scruffing my shoes through fallen leaves, crisp as fresh-picked apples. The most famous of the lines have become a mantra for many:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

I’ve mused upon those lines numerous times in my life, imagining the “what ifs” of the choices that led me to where I am today, or if I had any free will at all, as my son Ian (the philosophy and math major) has pondered with me. Each fork I selected (or not?) in a road, trail, or path reflected who I was at a juncture in life.

When I think back to momentous forks, the first was to pick the University of Oregon rather than remaining in New England where I’d attended high school. Indeed, that decision “made all the difference” and set me apart as an outlier in my graduating class at Concord-Carlisle Regional High School. Fellow students mispronounced Oregon as Or-y-GON and joked about covered wagons and the Wild West. I was undeterred and a little sorry for them. Since living under the shadow of Mt. Rainier National Park at the age of eight and nine, I’ve carried a deep love for the immense coniferous forests, peaks, and wildness of the Pacific Northwest.

After finishing all my high school classes halfway through my senior year, I set off for an adventure to work as a Volunteer in Parks at what was then Chaco Canyon National Monument. The journey there was circuitous, first flying to Seattle and then visiting colleges by greyhound bus in Washington, Oregon, and California, before continuing on to New Mexico. When the entire women’s cross-country team greeted me at the terminal in Eugene, I was smitten. (Yes, running was a factor). If I’d stepped off alone and felt a bit lost, I might have taken another fork.

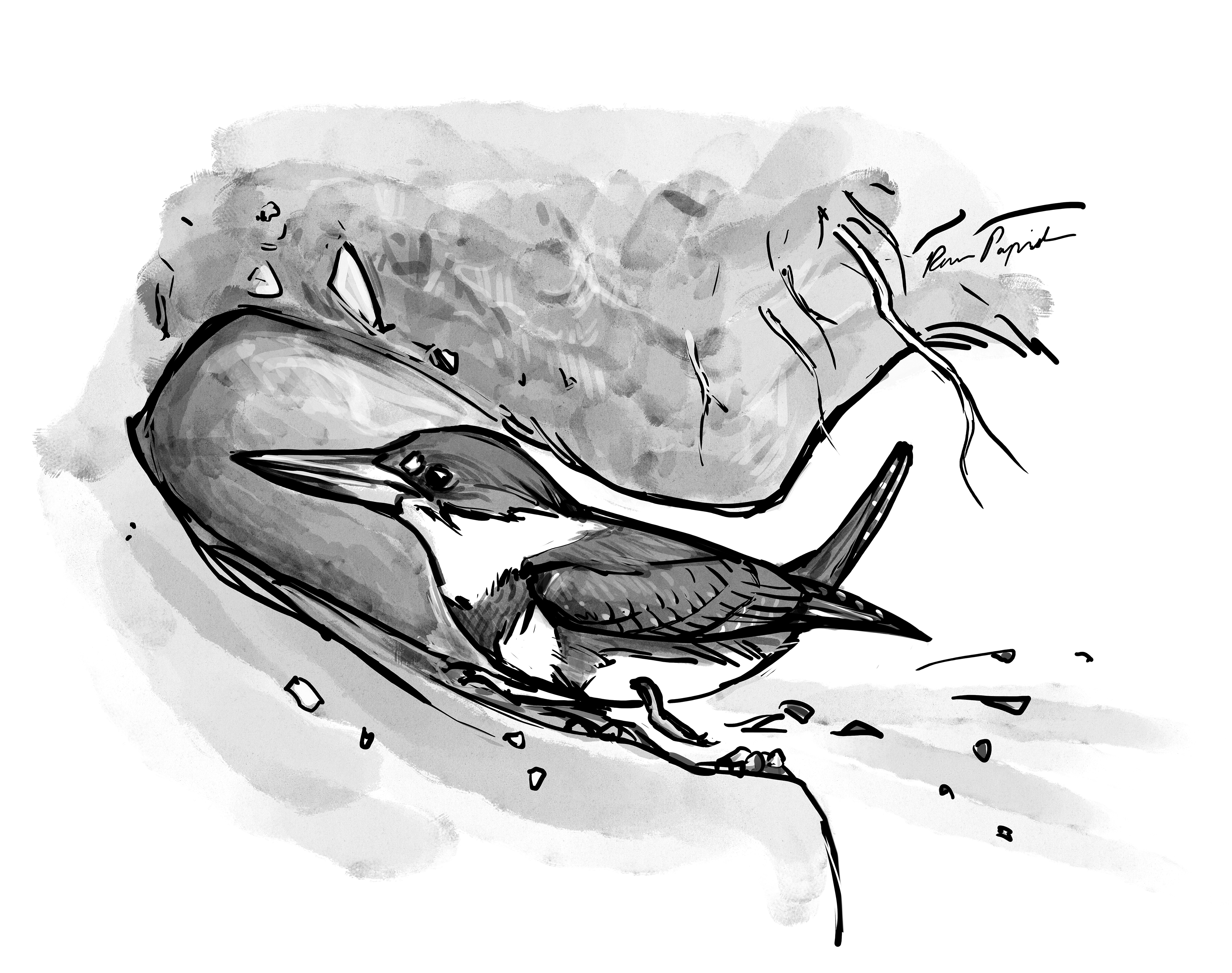

Today, I’m bound for Eugene to give a reading from my book, Halcyon Journey, In Search of the Belted Kingfisher. Returning to the city of my alma mater feels like a homecoming, and one that I could never have foreseen back in 1977 as a freshman there. I’ll be reading at 4 pm in tandem with the talented nature writer and herpetologist Tom Titus at Oakshire Brewing.

In honor of Eugene and New England (where I still feel rooted within hardwood forests), I’ll share a relevant excerpt from my book. This section follows the ecstatic moment of witnessing courting kingfishers on April 11, 2009:

“One hundred and fifty-three years earlier, also on April 11, Henry David Thoreau wrote, ‘Saw a kingfisher on a tree over the water. Does not its arrival mark some new movement in its finny prey? He is the bright buoy that betrays it!’

Traipsing after kingfishers reminded me of high school years in Thoreau’s home community of Concord, Massachusetts. There, I explored the hardwood forest behind our colonial home on Revolutionary Ridge, close to the Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House and not far from the Emerson and Longfellow residences. One day, I splashed through a woodland bog to reach a floating island of sphagnum mosses interlaced with predacious pitcher plants and sundews. Dwarf tamarack trees grew from the earth, which shook and rolled beneath my rubber boots.

Surely, no one else had been there, except Henry David. I’d found one of his notations from February 1, 1858: ‘When the surface of a swamp shakes for a rod around you, you may conclude that it is a network of roots two or three feet thick resting on water or a very thin mud. The surface of that swamp, composed in great part of sphagnum, is really floating.’

Years later, Gowing’s Swamp would earn protection as a natural area, credited as the one bog in New England brought to light through literature, specifically Thoreau’s journals. I credit my father for teaching me the art of the bushwhack early in life, which often led to off-trail wonders.

In fall of 1977, after one last summer job at home—planting, weeding, and harvesting bountiful produce grown on the fecund soils of an organic vegetable farm by the Concord River, I headed west to attend the University of Oregon. There, I would run cross-country and track until I left the team in favor of backpack trips, environmental activism, boy crushes, and a deep dive into the joy of hands-on fieldwork at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology. I would go on to live in northeast Oregon with my conservationist boyfriend and lobby for the passage of the Oregon Wilderness Bill of 1984.

The westward journey was inevitable. Thoreau guided me to Gowing’s Swamp, yet it was preservationist John Muir who epitomized the craggy western peaks that held me spellbound since Mount Rainier. The words below my yearbook photo with my short curly hair and earnest freckled face set me apart from most seniors with their cool quips.

Instead, I quoted Muir: ‘Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while the cares will drop away from you like the leaves of Autumn.’

Muir and Thoreau’s writings, my father’s constancy of spirit, and now Paul and Lisa all accompanied me as naturalist mentors on the kingfisher quest. Like Thoreau, who “traveled a good deal in Concord,” I was spending more time along the creek than ever before. The reward? I would follow a pair of kingfishers throughout their entire nesting season, or so I presumed.”

That expression on your face at age 8 is classic – and priceless. 😄

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hah! I agree…

LikeLike

This old dude is blessed to still encounter those diverging trails.

In the two weeks the trail of a sparrow search on a foggy morning suddenly diverged in the lifting fog to a flash of yellow and red and a never seen and photographed Intergrade Yellow-shafted x Red-shafted Northern flicker and his Red-shafted companion.

A week later in the same protected wildlife habitat the sparrow trail suddenly diverged and I was watching and photographing a Black-billed Magpie and an American Kestrel taking turns chasing each other accross a blue fall sky.

The sparrow trail that morning diverged from the usual suspects, White-crowned and Song Sparrows to lead to Lincoln’s, Savannah, White-throated and Swamp Sparrows. All topped off with a heaping helping of skulky Marsh Wrens posing, ever so briefly, for the camera that day.

All in a place that I have in some small ways helped with the conservation of those diverging trails.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful, Ken! Love the diverging bird trails and your descriptions–here’s to “skulky” Marsh Wrens !

LikeLike

Such a delight to settle in for a quiet read of your next Kingfisher Journal entry. It always contains visual pleasure, naturalist insights, amazing word-smithery, and a bit of education. Is it possible to over praise? If so, too bad…. I just love, love, love reading you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m with Gail! xoA ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person