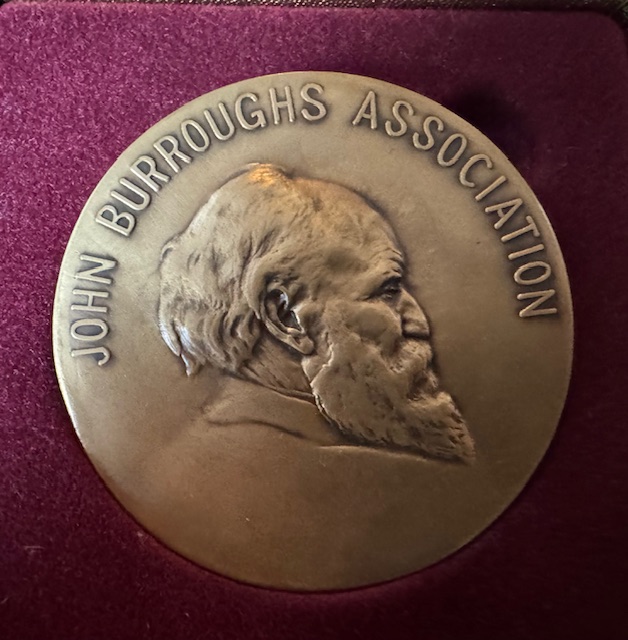

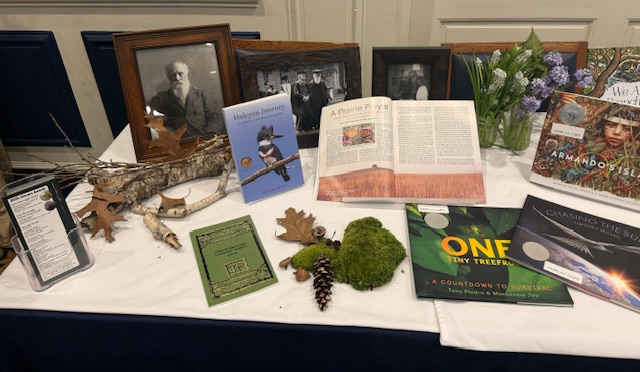

As April comes to a close, I’m reflecting on the momentous event of my writing life. On April 1st at the Yale Club in New York City, I received the John Burroughs Medal for distinguished nature writing. I am humbled by this recognition. Halcyon Journey, In Search of the Belted Kingfisher joins a long line of books awarded since 1926 in honor of the great naturalist writer John Burroughs. His book of essays titled The Art of Seeing Things helped teach me the art of close observation.

In fact, in an earlier version of my manuscript, I had written of Burroughs directly:

Like playing a musical instrument, the art of seeing takes constant honing, and my skills were rusty compared to early American naturalists like John Burroughs (1837-1921). Reading his essays collected in the book, The Art of Seeing Things, I’m reminded how far I have to go to truly “see.”

Burroughs often compared nature and books, two of the things he valued most: “If I were to name the three most precious resources of life, I should say books, friends, and nature; and the greatest of these, at least the most constant and always at hand, is nature.”

For Burroughs, nature was always at hand—he spent hours wandering as Thoreau did, often not far from his home in the Catskills of New York but reading every natural tiny footnote in the wilds underfoot. In the blind, I was forced to stop skimming through nature as I do so often on a run, and to read the fine print, as Burroughs described:

“The book of nature is like a page written over or printed upon with different-sized characters and in many different languages, interlined and cross-lined, and with a great variety of marginal notes and references…it is a book which he reads best who goes most slowly or even tarries along by the way.”

In the three months preceding the event, I thought long and deeply about what to say in my acceptance speech. While writing, I felt an imaginary presence of a kingfisher perched on my shoulder (very unkingfisher-like). I took the platform seriously. How could I share what the years following kingfishers on Rattlesnake Creek meant to me? How did that experience deepen my commitment to saving wild nature? When I stood up at the luncheon’s end to give the talk, my bird muse was there urging me on. I’m humbled to share my words here in a video (that includes an impromptu introduction) and the written words below.

Acceptance Speech, John Burroughs Medal

Thank you for this great honor of receiving the John Burroughs Award. I am grateful to all the people who helped me over the course of my decade-long journey of tracking kingfishers, writing, revising, and at last publishing with Oregon State University Press.

Whenever I faltered, the jay-sized bird of the headfirst dive urged me onward. I would hear that musical staccato volley of notes skipping across the creek, and I would vow to keep my promise. For above all else in my story, I wanted the kingfisher to emerge as the star of the show.

I’m imagining a queenfisher with us in this room, perched on a chair. She’s decked out in her fine cinnamon-red sash and belt across her white chest. We could ask her, “Why are you more colorful than the male, so rare in the bird world?” She might shrug in a bird way and say,” Why wouldn’t I be?”

When I lived and breathed kingfishers on a home creek in Missoula, Montana, I often dreamed about them. One time a kingfisher landed on my outstretched hand, and we spoke to each other in the language of birds. Some might call my quest an obsession. I came to think of that time as love extending from the bird to a community of life I would never have known otherwise.

Once, when sitting still on a warm September afternoon at the creek’s edge, a chocolate-hued mink rippled right over my bare legs. I had become another root—one with the cottonwoods, ponderosas, alders, and willows.

Returning to the queenfisher in this room, she would peer at us with those alert black eyes sighting down her dagger beak. We would admire her sassy crest and the neat flicks of her short tail. But the kingfisher is one skittish and elusive bird. Her realm is not this room, but fish-filled waters, sky, and a vertical earthen bank to excavate a nesting burrow.

The belted kingfisher remains my muse and spiritual helper in the way of the origin myth of the Arikara of the upper Missouri. When the people left an old world to find a new one, they were helped by three birds—an owl, a loon, and a kingfisher. This great kingfisher laid a beak across a chasm for the people to cross. The Arikara had a choice to continue or to stay and be transformed into the bird that helped them.

Transformation is a theme throughout my book. In the Greek myth, Halcyon and Ceyx were turned into kingfishers by the gods. Ancient myths of many cultures are filled with this easy slipping betweenness that links us to our animal kin.

We can return to the old myths. We can find a way of transformation in nature. We need not go far. We need not be experts. But we do need to mend our broken links to nature and in the process gain the determination to act on behalf of our fraying living world and a million species at risk of extinction.

The planet depends on our preservation of big wild places and of nearby wildness—like Central Park here in New York City. I have an affinity for a wooded gem in the southeast corner of the park—the Hallett Nature Sanctuary, named for my Great Uncle George Hallett, a civic leader and an avid birder. He took my father, Dave Richie, and his brother to Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and fostered my dad’s love of birds.

When I perched by Rattlesnake Creek observing a pair of nesting kingfishers from within a camouflaged blind, my father’s spirit was often present. Huddled under a Douglas-fir in a spring snowstorm with fingers too numb to write in my journal, I felt him cheering me on, reminding me of the quality of endurance we shared as long-distance runners. I healed there from his death from cancer far too young at age 70.

Nature has healing ways when we observe closely, stay quiet, and return often. However, it helps to have a guide to lead us through the tangles where wonder awaits on wafting swallowtail butterfly wings.

I ask each of you, who is your kingfisher calling you out into this wild world?

John Burroughs applied the word “guide” to the kingfisher specifically in his essay, “The Halcyon in Canada.” Many thanks to Joan Burroughs for referencing this fitting quote in her announcement of the award:

“The halcyon or kingfisher is a good guide when you go to the woods. He will not insure smooth water or fair weather, but he knows every stream and lake like a book, and will take you to the wildest and most unfrequented places.

I echo those last words—the wildest and most unfrequented places. While belted kingfishers will inhabit an urban creek or pond, I came to know the birds on a stream birthed in the headwaters of a designated wilderness safe from roads and chainsaws. Wilderness assured the creek ran cold, clear, and is still one of the last bastions for native bull trout.

In this time where we are fast losing unprotected wilderness, the kingfisher is the messenger calling us to preserve all that is left. On this 60th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act, let us hover no longer. Take the plunge. Work together. Call for more wilderness—for only in that protected state can we save our headwaters, our biodiversity, and the future for our children.

At the same time, we must rewild close to home, link animal corridors, and know that every wild pocket matters. Whenever we falter, the kingfisher will be there cheering us on.

Thank you.

Almost a month later, my heart is full of gratitude for Joan Burroughs, the great-grandaughter of John Burroughs and the head of the John Burroughs Association. When she called me with the news last December, I was in the field on a Christmas Bird Count in Sunriver, where our group received the gift of witnessing a great grey owl fly across a forest meadow. I immediately muted the unknown New York number. After three days and two more calls (forgetting to check voice mail), I finally answered.

When I heard Joan’s words–Halcyon Journey won the Burroughs Medal–my knees grew weak. I sat down breathing hard and feeling light-headed. How could this be possible? As the ceremony approached, Joan and I would converse at times and I’d feel her comforting presence. I would be fine speaking up, she assured me. These are our people attending the awards. Nature writers. Appreciators of literature. Lovers of wildness. And yes she might cry (there would be some tears).

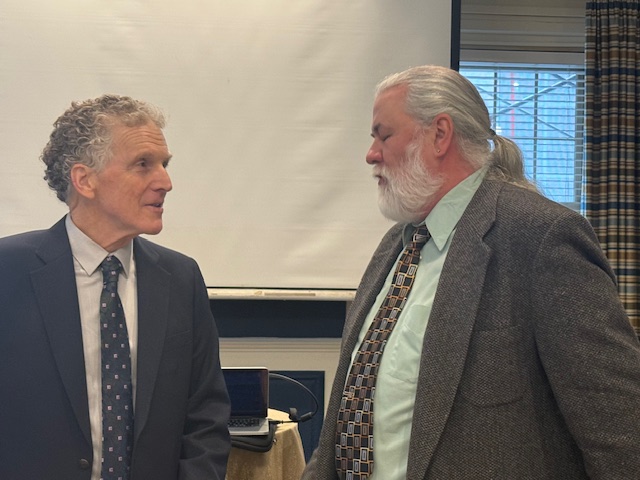

It was an emotional event held in this dangerous time for the planet. Yet, in that room of 60 sympatico people, I felt a resonance of joy, as if the walls could melt away and drench us in birdsong from Central Park a mile away. There, at the “Kingfisher” table of the luncheon with friends, family, Burroughs Association judges, and Oregon State University Press acquisition editor Kim Hogeland, I was also thrilled that Georgia Silvera Seamans joined us us later in the ceremony, after a class she had taught. Georgia interviewed me for her wonderful podcast, Your Bird Story.

I felt beyond inspired by the other award winners in the room. The Riverby Awards recognize outstanding children’s books on nature. In a social gathering the night before led by Joan Burroughs, we signed each other’s books and shared our stories. Among all those wonderful artists and writers, I clicked immediately with a favorite author, Sy Montgomery, who wrote The Soul of an Octopus among many books for adults and children. I highly recommend all the children’s books earning awards. Sy’s is the The Book of Turtles, illustrated by Matt Patterson. The nature essay award went to Gary Noel Ross for his piece in Natural History magazine, “A Prairie Royal.” When he spoke of his lifelong passion for butterflies at the luncheon, there wasn’t a flutter in the room. We were spellbound.

The best way I can end this reflection of gratitude is to stand aside for Rachel Carson, When she received the Burroughs Medal in 1952 for The Sea Around Us, she spoke these words:

“The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us the less taste we shall have for the destruction of our race. Wonder and humility are wholesome emotions, and they do not exist side by side with a lust for destruction.” —Rachel Carson, speech accepting the John Burroughs medal

A gre

LikeLike

This is such a wonderful and well deserved award, Marina! Your speech is transcendent. I’m so happy and proud for you. This afternoon, I will walk along the creek up to the old dam site and maybe a kingfisher will lead the way.

Much love and admiration from your longtime fan,

Connie Poten

LikeLiked by 1 person

Inspiring, Marina, and that’s just the first word that comes to mind while reading your blog. Thank you for your courage and commitment in completing this pilgrimage and for focusing on my favorite bird – the belted Kingfisher. We will keep your book in a favorite spot on our bookshelf, as proof that our communal efforts on behalf our natural world really do yield never-forgotten rewards.

Friend, Mike

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, congratulations! Such a well-deserved and impressive achievement. You’ve joined some revered authors and thinkers with that win. Thank you for sharing your beautiful writing.

LikeLike

Great speech ! What a great honor. Looking forward to reading/hearing about your time at Slabsides. See you in Boise Tomorrow night.

This might get duplicated since I hit a wrong button before logging in,

LikeLike

Congratulations, Marina! The John Burroughs award is richly (no pun intended!) deserved and earned by you. What an amazing achievement and experience. Your acceptance speech is deeply felt and just right. Thank you for including it here. Reading and listening to it was almost as good as being there.

LikeLiked by 1 person